More Information

Submitted: 30 April 2019 | Approved: 07 August 2019 | Published: 08 August 2019

How to cite this article: de Becker E, Dechêne S. A Belgian program to fight child maltreatment: The “SOS children” teams. Arch Psychiatr Ment Health. 2019; 3: 032-041.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001008

Copyright License: © 2019 de Becker E, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Abuse; Sexual abuse; Multi-disciplinary; Negligence; Network

A Belgian program to fight child maltreatment: The “SOS children” teams

Emmanuel de Becker1 and Sophie Dechêne2*

1Cliniques Universities Saint-Luc, University Catholique de Louvain, Avenue Hippocrate, 10, 1200 Brussels, Belgium

2Professor, Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, Catholic University of Louvain, Coordinator, SOS-Enfants Team, Cliniques Universities Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium

*Address for Correspondence: Sophie Dechêne, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department, Catholic University of Louvain, Brussels, Belgium, Tel: +3227642093; 3227642090; Email: [email protected]

Child abuse remains a complex issue affecting individuals, families, groups and society, and one which WHO prevalence figures show as a significant ongoing problem. The nature of the abuse, be it physical, sexual, psychological, or neglect, places the child at high risk of experiencing the multiple sequelae of the trauma. Depending on the child’s country, the disclosure of abuse by the child or a third party will either be moved into criminal justice system or directed to the medico-psycho-social sector.

In 1985, in Belgium, specialist teams were established to evaluate and support situations involving child abuse. More than thirty years later, we considered it opportune to update the parameters that our team has developed based on four reflexive themes. The first discusses the transformation of our society, families and individuals, exploring how each influences the others. The second theme describes the diagnostic process, holding in mind the complexity of any situation. The third theme describes the reasoning behind these teams, considering this as a de-judicialisation of such situations. Finally, we describe the different treatments available. This paper describes the evolution of clinical practice including developments in several aspects that have arisen through handling situations of abuse.

In the light of epidemiological data collected by the WHO, despite many prevention and awareness campaigns and training programs, the prevalence of child abuse remains highly significant. According to numerous studies, almost one in four women and nearly one in six men report having been sexually abused before the age of eighteen. Child abuse remains a complex issue involving multiple components, whether individual, family, group or societal. Therefore, its evaluation and treatment require consideration of the medical, social, psychological and legal aspects of each case [1]. There is no such thing as a light or a serious situation, any transgression is liable to have harmful repercussions in the short, medium and long term. It is therefore essential to respect a rigorous and respectful evaluation period for the child and those around him. Depending on the country, the revelation of abuse by the child or a third party will be either “judicialized” or directed to the medico-psycho-social sector. In Belgium, in 1985, following an action research conducted by various university faculties (Medicine, Law, Psychology), an initial decree established teams (“SOS-Enfants” Teams or, in English, SOS Children Teams) to assess and treat situations of child and adolescent abuse. This was followed by two decretal arrangements, one in 1998 and the second in 2004, which specify, among other things, the composition of the team and the scope of tasks, such as ensuring the care of minors who have committed offenses of a sexual nature.

Through this article, we offer a consideration of the tool represented by an SOS-Enfants Team, looking at parameters related to social development. In 1997, one of our books proposed benchmarks for the assessment and treatment aspects of child victims of sexual abuse, and of their families [2]; in 2018, it seems appropriate to update the aspects developed in our earlier work by using case reports which, without being paradigmatic, illustrate the point.

General considerations

Abuse is an age-old phenomenon. Through stories, we realise that children have always been victims of ill-treatment in all sorts of ways. For a long time they were objects, exchange goods, production agents, and were hardly taken into consideration. If, in ancient times, a father had a right of life or death over his newborn, in the middle Ages the child was perceived as a human being fundamentally endowed with mischief or evil, raising suspicion. This perception of the child’s condition called for regulatory measures, dictated by, among other entities, religious institutions. In the nineteenth century, the child was still subject to educational dictatorship if not put to work at a young age. However, at the end of the 19th century, the concept of abuse began to appear in legal texts. In 1950, in the United States of America, the notion of “beaten children” shed light on the lived reality of the child; the reality of the real body objectively flouted, and an awareness of the child’s experience. In 1989, the International Convention on the Rights of the Child recognised the child as an object and subject of the law. At the end of the twentieth century, allegations of abuse were indeed taken into consideration, albeit sometimes in a simplistic manner, with the corollary of the designation of a new culprit of all evils (“scapegoat”) in the person of the paedophile. Thus, for centuries, the child has been the one who does not speak (“infans”) and was unable to enjoy a status of his own either through his own words or actions. Psychoanalysis and psychodynamic approaches have led to real advances in the understanding of the human being’s psycho-emotional development, except in regard to the voice of the child. It was considered prudent to be wary of anything the child might claim, as this could reflect his fantasies as well as his potentiality as a “polymorphous perverse”. In recent times, the child seems to have been better recognised and protected, even if abuse still exists and some still hesitate to believe this. Adult movements have and are being set up so that children are better respected in terms of their basic needs, which are divided along four axes. The primary needs concern physical well-being in its various forms (diet, physical care, emotional warmth, etc.). The second axis deals with security, in its material and emotional aspects; dimensions of stability, regularity, and coherence are included. The third following point is about boundaries: it is essential that the child meet adults who, in a firm and affectionate way, articulate and enforce a line of demarcation between sociability and egocentrism, demonstrating the importance of containing the more serious of our personal impulses and our most unacceptable desires. Finally, the fourth axis is spiritual: the child, in order to build himself up, to gradually form his identity, wants to be valued, encouraged, and recognised as being kind, to be listened to, to share thoughts with adults. It is through the demonstration of all of these in the socio-familial environment that this goal can be realised. As a result, the child will gradually establish his singular and unique place in a community, becoming a person with a solid and secure base, and a well-developed sense of self-esteem. Parents, the main figures of attachment and education, are therefore expected to exist in the manner of one of the various forms of parenthood. “Good enough” ... good but not perfect, the adult is involved in the child’s development at all levels.

This helps the child, among other things, to progress towards a personal ideal, even if, like the end of the rainbow, it grows further away as the pursuer moves towards it. Situations of psychological neglect and abuse highlight shortcomings in these basic needs.

Some definitions

In addition to negligence, several categories of abuse are schematically defined according to its physical, sexual or psychological nature, as well as stating whether it takes place in the family circle or outside it. It is important to recognise that this differentiation is confronted by complex clinical realities, usually incorporating several forms of inadequacy and failure with respect to behaviour towards the minor. For the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (excerpt from Article 19, 1989), mistreatment includes any form of violence or brutality, whether physical, mental or sexual, neglect, or any form of exploitation. In 1999, the WHO adopted the following definition:

“Child abuse or maltreatment constitutes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power”.

In Belgium in 2000, the Federation of SOS Children’s Teams deemed that maltreatment concerned any physical injury or mental violation, any case of sexual abuse, or the neglect of a child that is not accidental in nature but due to the inaction of the parents, or any person exercising a responsibility over the child, or abuse caused or allowed by a third party, which could lead to the damage of the child’s physical or psychological health. As we observe, there are nuances depending on the sources and authors. According to our experience, and following the work of Haesevoets, we consider mistreatment any attitude that does not take into account the satisfaction of the needs of a child and thus constitutes an important obstacle to his or her development [3,4]. Abusive behaviour can be intentional, or the result of negligence or social failures. Abuse covers different meanings and includes a wide variety of semantic ranges: martyred children, beaten, in mortal danger, suffering gross negligence, belonging to a family at risk, shaken babies, cases of torture, confinement or institutional violence, child slaves, sold or for sale, child victims of abandonment, infanticide, street children, child victims of paedophilia, prostitution and child pornography, child victims of excessively rigid education, children living in perverse relations with adults, victims of abuse of power, sexual assault, trauma, or chronic child abuse. In recent years, we have found the concept of “well-treated” to be vaguely defined. There is a risk in using this word given the “categorisation” (good/bad) that it entails. Any such separation, for example, within family groups, questions the ethical position of professionals, since it is difficult to define a “normal” family and any group dynamic is essentially evolutionary; we are far from a binary logic when it comes to intrapsychic and relational human functioning. Moreover, and certainly in our time, it is necessary to acknowledge a degree of cultural difference; for example, Kazat mothers in Central Asia and Yakuts in Siberia masturbate their young child to appease them, this approach being quite accepted in their community. The response would be rather different in Europe.

As for incest, many authors propose various definitions, from the broadest to the most specific. Thus, Kempe and Kempe, in 1978, consider that it is the involvement of dependent children and adolescents, immature in their development, in sexual activities of which they do not fully understand the meaning, thus violating taboos about family roles [5]. For Strauss and Manciaux, in 1982, incest is the participation of a child or adolescent in sexual activities that he or she is unable to understand or that he undergoes under duress, or sexual activities that transgress the social taboos that exist in almost all societies [6].

In 1984, Furniss and his colleagues argued that incest is any form of child abuse by any adult parenting in the family context [7]. Following Sgroi’s expanded definition in 1986, intra-familial sexual abuse or the incestuous sexual exploitation of a child is the imposition of any form of sexual act on a child or a teenager by a parent, a step-parent, a member of the extended family, a substitute parent figure, or an educator. Authority and power can constrain the child to sexual submission [8]. Hayez and de Becker, in 1997, consider incest to be a sexual relationship that brings into contact people between whom marriage, or sexual union in general, is legally impeded by kinship (which also includes siblings). Such a relationship can be formed between a minor and a relative or similar figure [2].

An original tool: the SOS-enfants team

In 2018, out of fourteen SOS-Enfants Teams in the French-speaking part of the country, three, ours being one of them, are currently integrated into general hospitals. A SOS-Enfants Team, created to help and care, is a group of specialised professionals, recognised and subsidised by the State to fight against all forms of abuse. On average, an SOS-Enfants Team is composed of 6.5 full-time equivalents (FTEs); it includes social workers (2.3 FTEs), psychologists (2 FTEs), a lawyer (0.5 FTE) and doctors (paediatrician (0.5 FTE) and child psychiatrists (1.2 FTEs)). It collaborates regularly with other structures, including public social services, and reports situations to the judicial authorities where it deems this appropriate.

The SAJ is an administrative and social body set up in 1991 to design a “de-judicialisation” of the protection system for minors; the collaboration of people concerned about or involved with a child or a teenager in difficulty is therefore necessary. The explicit agreement of a young person of more than fourteen years is required. The aim is the establishment of an assistance program adapted to the difficulties stated above. The SAJ can also perform a third-party role in families encountering difficult and isolating situations by mediating during confrontational exchanges between members. In the case that there is no collaboration from the family and the SAJ considers the child in danger, the body will inform prosecution services and the judicial protection process can then start. The latter can impose any measures, unlike the SAJ, which must negotiate any actions to be implemented [9]. The SOS-Enfants Team also works in a care network by coordinating with other institutions involved. In short, it carries out a complete psycho-medico-social assessment of any child referred to them, along with his relatives, before proposing pedagogical, social, and therapeutic support.

Each situation encountered is singular, marked by the various negative effects of the tragedy of abuse. Here we recount three that, without being paradigmatic, illustrate our point. The objective is not to analyse the different aspects of care but to pinpoint some elements to support the theme of the article.

Case report 1: Mehdi

Mehdi is eight years old when the school doctor requests our intervention following the discovery of multiple bruises on his body. During the examination, the child confides that both his father and his mother hit him regularly with a belt. After establishing an evaluation framework with parental consent, we will have the opportunity to meet Mehdi alone and with his family. Shocked, saddened, and worried about the consequences of what he has told us, the young boy explains that he does not understand all the reasons for his parents’ blows. He understands that he can be boisterous, silly, and tell lies. It seems to him, however, that he receives blows when his father drinks, during serious marital disputes, or during siblings’ fights. Mehdi sees himself as a scapegoat in his family. While his parents cannot deny hitting their son, they believe it is educational, and respects family traditions, especially as the child is difficult. For his part, Mehdi, while he understands and excuses the parental actions, suffers and considers himself a victim of injustice. Through his words, we can see that he is serving as a projection surface for the frustrations and dissatisfaction of adults. With each parent we will carefully approach the issues of authority and law, while respecting their rites, tradition, and religion. The therapeutic goal is to model family relationships, through clearly defining roles and avoiding the use of violence. Low-key subsequent support work, including providing help to the parents, will allow, after six months, the establishment of positive interactional patterns. One day, however, Mehdi, relying on the framework of the clinical intervention, threatens his parents by saying that he will go to the police if they reprimand him harshly or if they do not give him what he wants. In his own way, the child is trying to take power, therefore no longer respecting parental authority. A crisis re-emerges, aggravated by a risk of dysfunction and maltreatment.

We toned to reiterate the multiple variations of what “law” signifies through speaking clearly of the rights and duties of each party with both the child and each of the parents. In order to avoid harmful acting out, personal and group development sometimes requires sustained support from clinicians over time.

Case report 2: Felix

Felix is sixteen when we meet him for the first time, he is accompanied by his mother. She requires an assessment because one of her friends has accused Felix of sexually touching her six year-old daughter. The events reportedly took place during a holiday with several families. The sexual assault was allegedly repeated at night during the same holiday. The mother is turning to professionals to try to understand, not knowing who to believe, her son or her friend, the mother of the potential victim. Listening to his mother’s desire to understand the situation, Felix adopts a closed attitude, staring at the floor and murmuring: “That’s wrong, I did not do anything. She’s a liar ... it’s a plot.”

The teenager denies the facts as a whole, claiming that this is an act of revenge against him engineered by the older sister of the so-called victim. Different meetings are then proposed, individually and as a family. By family meetings, we mean meetings between Felix and his mother since he is an only child and he has never known his father. We also learn that the mother is in a homosexual relationship, information that will also be revealed to Felix by our team during the follow-up.

Felix is a young man who is uncomfortable with himself, willingly isolating himself in his room, immersed in his music and screens. His mother recognises that her son is “escaping” from her and feels that she is finally satisfied with the implementation of a therapeutic process. However, as much as Felix speaks of existential issues, of certain elements of his history that remain nebulous for him, he will never leave his defensive position and his hypothesis in relation to the events that “sent” him to the specialised consultation. He says that he is hurt by these accusations that harm his reputation. During individual meetings, Felix, relying on the relationship of trust with the clinician, gradually evokes his fears, his doubts, but also his attraction to girls of his age.

It should be noted that the six-year-old identified as the victim is met by other colleagues who believe her allegation is reliable. Despite our attempts to learn more about the event in question, Felix will retain the same attitude and version of events as he did at first. This being the case, it seems to us illusory and not constructive to confront the teenager with this impression of events, designating him as an aggressor. Felix would simply employ distancing mechanisms and denial. Rather than pursuing of the conclusion of the investigation as to the materiality of the facts, we opt for general therapeutic support. It is not impossible that sexuality may one day be more directly addressed, if the transferential link is sufficiently established. After three months of support, Felix still refuses to take additional projective tests. Although dreading to discover himself or to be discovered, he agrees to continue with the individual therapeutic meetings. In this case report, the question of diagnosis remains complex. How to describe this young person in any other way than “a young person going through an adolescent process, in search of identity, having probably experienced sexual acts with a child younger than him”? Certainly there has been transgression, but, it seems, without violence in the sense of a desire for destruction. It would also be interesting to explore the aspects of object relation, the empathic capacities as well as the notions of guilt, responsibility, and as a corollary of possible reparations. We are faced with a young person who displays an interiorised law and real societal values but who, at the same time, goes through periods of doubt, of not understanding who he is, searching for a male identificatory model (the quest for the absent and missing father), a self-ideal, and life project. The therapeutic challenge, therefore, consists in accompanying him in a search for the meanings behind an inappropriately-exercised sexuality.

Case report 3: Georges

Georges had just turned twelve when we met him in the emergency room of the hospital where our team is located. Originally from Central Africa, he was brought in by his mother and sisters panicked by his loss of consciousness. While in casualty, during somatic investigations, the adolescent wakes up abruptly, refusing the lumbar puncture that was about to be performed. In a deep, firm voice, Georges says, “I’m fine. Do not touch me. You are not to put this needle into my body ... “Perplexed by this change in attitude, the emergency team calls for the rapid intervention of a child and adolescent psychiatrist. During the first contact in the presence of his mother, the adolescent, in a state of obvious stupor, and avoiding eye contact, answers a few simple questions with difficulty. His attitude hardly changes during a brief individual meeting. At the same time, the mother describes the general context. The family had to leave their country of origin hastily for political and economic reasons. Georges is the youngest of four siblings, preceded by two years by a sister diagnosed with autism. The teenager seems to have acutely changed his behaviour for about a month. Previously, he had been considered a reserved, studious boy, who respected the rules, and was maybe even a little too “compliant”. The young person then became “strange”, showing new anxieties, and questioning his mother about sexuality. The mother remembers some very astonishing affirmations like: “Mum, I’m afraid of raping someone ... Should we always have sex with violence and force the other person to have sex? ...”. During the assessment, we also hear that Georges has recently presented with disturbed mood, sleep, and appetite. The father, who joins us later, relativizes the maternal anxieties. He puts these different declarations down to adolescent transformation. However, the parents accept an assessment of their child, insisting on outpatient care, based on the young person’s support by the significant family network. Individual and family meetings, involving the psychiatrist and the psychologist, the latter proposing that projective tests be taken, are not followed by an amendment of the symptomatology. On the contrary, George is more and more disrupted and incoherent, his mental state evoking the beginning of a psychotic process. After five weeks of trying to manage him in the outpatient clinic, hospitalisation becomes unavoidable, with the family supporting this option. However, the father does not change his mind about the cause, expecting a full and rapid recovery of his son’s mental illness. Throughout the deterioration of his mental state, Georges presents a very high level of anxiety with narcissistic wounding. His mental state shows some mood instability switching from laughter to tears, his thought process shows erratic thinking and thought blocking. His speech shows that the delirious content of his thoughts is filled with fear. Eventually, the medical team resorts to treating him with neuroleptics. During the various assessments, Georges talks about his apprehensions of being sexually assaulted or having to rape children himself, driven by inner voices that he cannot counter. Contact with professionals is feared by Georges and only the presence of his mother seems to soothe him somewhat. Both somatic investigations and interviews with a psychologist do not provide any evidence about a possible aetiology. Moreover, nothing from the cerebral investigations allows us to understand the degenerative process. Despite our different attempts, we were unable to highlight any specific traumatic event other than his family’s expatriation as a precipitating factor. Then, quite suddenly, after five weeks as an in-patient, Georges shows a reversibility of the symptomatology. In view of his young age and the rapid change of his mental state, we decided to gradually discontinue the medication. Therapeutic support can then continue in an outpatient setting, with the young person finding his bearings and his routine, both at home and at school. Many questions remain at this stage. Intra-psychic reorganisation around questions centred on physical transformations, identity research, and both narcissistic and objective investments; could these have led to the intensity of the psychiatric symptoms displayed by this young adolescent? Slowly through individual and family meetings, Georges talks about his intimate relationships and his history, as well as his anxieties. He talks about the upheaval he experienced during a school trip; on the bus, a boy apparently trapped him in the seat, miming sodomy in front of other teens and giving Georges huge embarrassment, leaving him speechless, and unable to react. He was mocked and the teacher who heard the scene from afar, according to George, trivialised the brief episode. The teenager had never mentioned this event to his family, having probably tried to repress it, fed by shame, guilt or both, failing to understand the impact it had had on him at the time of his acting out and displaying the symptoms detailed above. The behaviour experienced as an aggression had traumatic value for this young person, especially as the assault experienced questioned the parameters of the body as regards sexuality and identity. And it is possible that the notions of pleasure, desire, and enjoyment, are not entirely removed from the troubles experienced by Georges. This report illustrates all the caution we must adopt in relation to diagnoses during adolescence, and even more so at this pivotal period of pubertal transformations entangled in intra-psychic and relational re-workings. The story of Georges is far from unique.

Case report 4: Melissa

Accompanied to the casualty department by her maternal grandparents where she was staying for a weekend, fourteen-year-old Melissa reported having been gang-raped during a walk alone in the local area. The emergency team colleagues ask for our intervention as an SOS-Enfants team. Shocked, almost mute, with no facial expression, Melissa is admitted to hospital to set up an effective medico-psycho-social support. We meet her individually then with her parents, who have hastily returned from abroad. During the first days of admission, she shows anxious agitation, changing mood, disordered sleep, and remains barely open to attempts at dialogue. United, the parents do not hide their dissatisfaction with the grandparents who, in their opinion, did not provide Melissa with sufficient protection. The judicial investigations are quickly put in place; the examination carried out by a medical examiner confirms that the teenager is no longer a virgin. Thus, during the first phase of care, the specialised team pursues the goal of supporting a situation of extra-familial sexual abuse, ensuring a caring presence for a young victim of a traumatic event that has generated acute and sudden symptoms. In addition, we meet members of her social and family environment. There are four siblings: an eighteen-year-old older brother, an eleven-year-old sister, and an eight-year-old brother. The family portrays the image of a solidary unit, anxious to “speak with one voice”, and not very open to the outside world. Two weeks after her admission to the hospital, Melissa surprisingly asks to “talk to someone”. Retracting from the allegation of gang rape, she confesses to being abused by her father since a young age, without being able to specify the starting date of the facts. She points out that she could not at first open up about this painful reality. As much as we had found it difficult to give some credibility to the reason for admission, the teenager seems genuine and sincere about the facts now alleged. She adds that she decided to come out because she caught her father trapping her younger sister against the wall, caressing her chest. She says she could not stand helplessly by and witness the repetition of this transgressive paternal process. In the wake of these new revelations, we meet the father accompanied by the mother. Head down, he acknowledges the facts, expressing his relief at having been found out and his guilt regarding such inappropriate acts. His wife, shocked at first, held his hand, stating loudly, “We got married for the better and for the worse.” Melissa’s revelations are not accompanied by any easing of her symptomatology. She remains agitated, anxious, begging for the presence of the nurses, and struggling with loneliness. One of the psychologists who meets her regularly feels that there is still some secret. A third stage in the allegations will occur one month after admission to the hospital. Melissa then speaks of her elder brother; for about a year he has been joining her very regularly at night and forcing her to have sex. Like his father, the elder brother admits, not without guilt, having used his sister as an object of sexual pleasure. Inhabited by a malaise since the beginning of adolescence, he presents an addiction to pornographic films, then acting on the body of Melissa as a form of discharging sexual energy. A major crisis then shakes the entire family group, resonating on members of the extended family. The respective grandparents intervene with force. The maternal grand-parents do not accept their daughter’s choice to support her husband by deliberately opting for the survival of them as a couple. The paternal grandparents decide to take a radical step away from the parents and their four children. As for uncles and aunts, they adopt inconsistent positions, all very emotionally-charged and generally not very constructive. For her part, Melissa, presenting an improvement in her anxio-depressive symptomatology, manages to relay the trauma in individual interviews. Discharge from hospital is envisaged with Melissa to be moved to a reception centre for young people. The possibility of a return home is entirely excluded since the mother stigmatises her as the instigator who pushed both the father and the brother to act. Once arrested, the father is incarcerated for a five-year sentence. The older brother is sent by the judge to a specialist centre, where he will benefit from care for young perpetrators of criminal acts of a sexual nature. For more than three years, we provide therapeutic support to family members, facilitating different meeting formats. To ensure continuity and coherence, the psychologist who welcomed Melissa during the first days of her admission, continues to support her and to help her through trauma elaboration and through working on the reconstruction of her identity. The mother, confronted with multiple socio-economic difficulties, maintains a link with our team through a social worker. We organise monthly meetings with the two youngest alone, in the presence of Melissa, or of the elder brother. During his authorised prison outings, we meet the father, who is willing to have therapeutic meetings with his wife in order to plan a post-incarceration life abroad. Two years later, Melissa expressed a wish to meet her father in our presence, with the intention of asking him about the ontogenesis of the incestuous process. Eventually, the father accepts some meetings during which he discusses the facts, thus explaining to his daughter that he began to make use of her body when she was only four years old. Overall, he keeps a discourse based on facts disconnected of affects, vaguely talking about excuses, insisting on his position as a victim within the prison. A few years later, we learn that Melissa, then aged 18, was sexually assaulted on the subway during a late summer afternoon. This new traumatic episode required emergency admission to a psychiatric hospital.

Figures

Without going into a detailed analysis that would require significant elaboration, we would like to pinpoint some key figures from our SOS-Enfants team. By multiplying these figures by fourteen, we can obtain data applicable to the French-speaking part of Belgium, which represents about 5 million inhabitants. The last five years have been marked by an increase of 3% per year in the number of reports reaching the team; in 2017 we recorded 476 reports. These are reports made by telephone on business days between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. This figure indicates that there is on average more than one call per day (transposition into working days). On weekends, holidays, and every day after 6 p.m., a telephone message directs any caller to our hospital’s emergency room. In 2017, among those who reported, 198 were non-professionals while 278 were professionals, mainly from the school network, hospital structures and the SAJ. In 27% of cases, it is the mother who makes the report, and in 18%, the fathers. 67% of the 476 reports will lead to the opening of a case file by an SOS Enfants team. The sex ratio of the children encountered shows a female prevalence of 52%. The age distribution is as follows: 10% for children aged 0-2 years; 13% for 3 to 5 years; 25% for 6 to 8 years; 22% for 9 to 11 year old, and 30% for 12 to 17 years old. In addition, 38% of children live with both biological parents, and 34% live with a single mother. Physical abuse affects 35% of cases, sexual abuse 32% and psychological abuse 20%. After assessment, the abuser is, in 88% of the cases, one or both parents. The duration of care is less than one year in 93% of cases.

In thirty-three years, the number of reports reaching the specialised SOS-Enfants Teams has steadily increased. Child abuse still exists. Since the “Dutroux affair” that rocked Belgium and neighbouring countries in 1996, awareness campaigns and training for professionals in the care and aid sector, as well as the judiciary, have been launched. Techniques and tools have been developed to meet the child with their best interest in mind [10]. In the light of the case reports, this discussion, without being exhaustive, will focus on four reflexive axes that we developed in the 1997 work. The aim is to show the evolutions of the practice with regard to the transformations that have taken place in many respects; we will concentrate on several focal points that include the handling of situations of abuse.

Societies, families, individuals

If we focus on sexuality in its numerous variations, it is obvious that the media is full of it, sex representing a gigantic market share echoing mentalities centred on the body and its image. Language and discourse are also threatened, often giving way to the pleasure principle. The primacy of primary narcissism is thus maintained in our societies in search of values and signifying carriers, to the detriment of otherness and distancing us from altruism [11]. This theory is known; however, the issue seems to have been growing over the years, even if reassuring exceptions would encourage an optimism that Braconnier describes as intelligent [12]. These aspects relate to the incredible advances of communication and information technologies, as regards their ease, accessibility and speed. More than ever, the modern man is caught in a spiral of impulsiveness and immediacy [13]. Another parameter to consider socially concerns the family, or rather, the families. Certainly, in large cities, the family unit covers different meanings, the nuclear family no longer necessarily constituting the reference statistically. To convince oneself, one just has to ask a child to draw his family. Corollary to these upheavals of society through plural family configurations, issues of couple dynamics in their aspects of responsibility, function and parental role continue to become more complex and undermine both mothers and fathers. It is not easy, in the twenty-first century, to ensure continuity, coherence, and consistency with a child. These parameters, which respond to their basic needs, are regularly lacking. Thus, for example, the child of today, if he is not confronted with the absence of father, meets different men, simultaneously or successively, assuming greater or smaller levels of responsibility. At the same time, out of excessive concern for the child’s full satisfaction, and certainly in the case of duality in the family configuration, the mother may sometimes indulge the child, confusing whim and need, running the risk of turning him into a child-tyrant. These developments contribute to the weakening of the third-party function participating in the establishment of an internal framework in the child’s psychological apparatus. These elements are brought together to see, as Barbier points out, “the fabric of a perversion” [14]. In general, if over the years neurotic functioning may seem less present, people presenting antisocial or borderline personality traits are now more frequently encountered than before. Continuing in this thought process, some are even made to believe that “manipulators are among us”[15]. Note also that clinical meetings or journal clubs evoking the psychopathology of patients invariably speak of such mental health disorders. Psychological construction is dependent on the environment just as it is influenced by human actions and language. Insofar as our communities change their way of being, so too does the individual progressively transform his or her worldview, interactional patterns, and defence mechanisms [16]. Logically, this results from the repercussions on the individuals met on the ground. In situations of intrafamilial sexual abuse, we find less and less neurotic structure in the perpetrator’s head [17]. These evolutions affect evaluation and treatment. In addition, our interventions are more frequently focused today on underage perpetrators. While the societal impacts described here may influence identity construction, among other things, in the tendency to act in an impulsive and/or instinctive manner toward sexual gratification, we also note the acting out of masked depressions. Many young people seem isolated, left behind, under-invested. On the side of the victims, the traumatic event will leave its mark in a patent or latent way; many cases with various clinical presentations are regularly encountered in our clinics. Thus, a “pseudo-conformism”, as reassuring as it may appear, will probably correspond to mechanisms of denial and distancing. While the destructiveness of abuse depends on a variety of personal and contextual factors, many complex symptoms during childhood and adolescence are rooted in abuse [18,19,20].

Diagnostic evaluation

As the case reports testify, the situations of abuse are complex and difficult to fully comprehend as it is necessary to consider various factors such as speech, behaviours, and interactions. The chosen model is based on two essential principles. The first corresponds to multidisciplinarity and, as a corollary, to co-operation and collegiality. Over the last thirty-three years, the different perspectives of the various disciplines have made it possible to construct an assessment of the possible materiality of the acts of abuse and their impact on the young victim and those around him. Each professional, in his discipline and his own speciality, participates in the completion of the diagnostic process, in the manner of assembling a puzzle, in order to achieve the most holistic analysis of the child in question and his socio-family environment. The synchronic and diachronic dimensions are always taken into account. Thus, based on the materiality of the facts alleged and/or observed, the diagnosis of maltreatment aims to qualify the condition of a child and of members of his family and friends, and to estimate the possible repercussions of the failing on individuals and relational functioning, in order to propose the most relevant therapeutic course of action. The second principle encompasses the methodological aspects of the process since several diagnostic fields are involved, each referring to specific adapted tools. Let’s look briefly at these by reflecting on how much the experience gained during these years has shown the relevance of a “flexible systematisation” in the investigation process. The first plan corresponds to the social diagnosis which consists of analysing the general context of the child and those around him, taking into consideration his culture, social anchoring, and socio-economic conditions. If maltreatment transcends all societal layers, precariousness is undeniably a risk factor. Systemic diagnosis completes the first exploration. Twenty years ago, Barudy proposed to “categorise” families through their so-called “mistreating” dynamics [21]. It is clear that today, while certain dysfunctional relational patterns can be found, abuse has run through multiple family configurations as they have evolved. Note, however, that the more chaotic, entangled, “off-limit” a family is, the greater the risk of an adverse event acting out. The instability of the family unit certainly leads to higher levels of child sexual abuse. The systemic evaluation consists in observing the role of an individual in his own system, observing the quality of the interactions, noting dysfunction alongside potential, and resources likely to be highlighted during the therapeutic phase. The third diagnostic plan covers the medical component; the somatic examination of the child tries to highlight the possible wounds, and to re-humanise the traumatised body if necessary. The paediatrician, a member of the specialised team, regularly collects specific answers, or even new revelations that the child confides in the specific setting of a meeting with “the man or the woman in white”. The therapeutic effect of this medical encounter on anxiety is far from negligible.

The psychological and psychopathological aspects represent the fourth part of the diagnostic process. The quality of the attachment, the individual functioning of the children and adults concerned, the presence of traumatic repercussions on the one hand, and mental disorder on the other hand, are some areas of investigation. It is essential to understand, among other things, links to attachment figures, and defensive mechanisms such as identification and projection processes. The multiple diagnostic procedures are put into effect using interviews supported by various media and certain examinations or tests [2,22]. The recording of the patient’s history will tell us if a previous assessment of the child has been made. Whatever the case may be, we are careful to situate the young person in the context of his overall development, using Brunet-Lézine and GED (Development Evaluation Grid, Laboratory of Infant Studies of Montreal) for this purpose. The entire cognitive component that of learning in general, is, of course, taken into account. As regards psycho-emotional assessment, the Rorschach, the CAT or the TAT bring precious elements both to the child and the adults in question, allowing us not to know the truth but to better understand the child’s psychological functioning. At the start of the care process, great importance is given to the child’s speech. For this purpose, we carry out a specific interview in accordance with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) method, built on open questions. Experience has led us to abandon the Statistical Validity Analysis (SVA) method, which is cumbersome and lacks international scientific validity. We remain convinced of the importance of daring to speak about abuse by meeting the child on the materiality of the events he has experiences, as long as the clinician has worked on his own resistance and prejudices related to transgressive sexuality. Today, the voice of the child has a social value that will see, if necessary, the intervention of judicial proceedings and potential criminal prosecution. But this speech cannot be fully guaranteed and secured, and the child can therefore not be held responsible for lacking notions of discernment and informed consent. It is also important to remember that there is a need to distinguish authenticity and credibility [22].

The care framework

The SOS-Enfants Teams were created in a spirit of “de-judicialisation” of situations of abuse. The legislator promoted the management of the patient in a system of help and care, free from judicial repercussions. The intervention of the specialised team is part of a broad-based network policy, based on Parret’s concept of the “partnership envelope” [23]. Over more than three decades, the landscape of bodies and structures potentially involved in situations of abuse has become more complex. Concomitantly, the professionals found a bottleneck in the general system of help and care as requests exceed the services available in view of the evolution of individual, family, and societal issues.

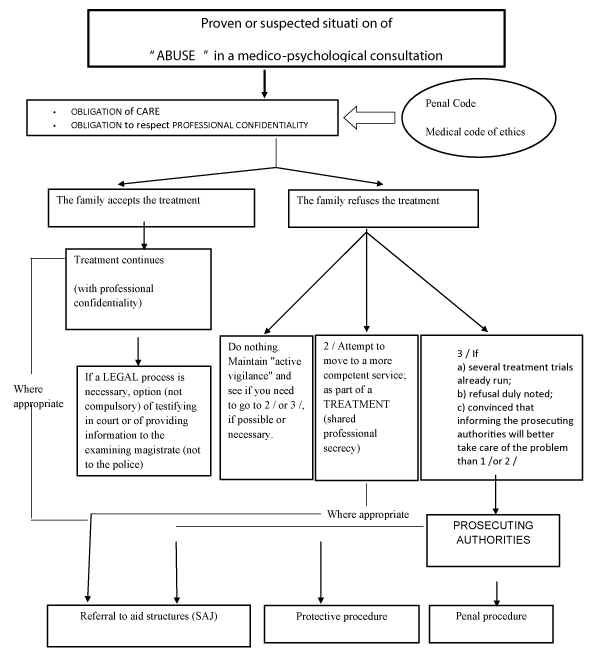

Today, paradigms and theoretical models are mistreated, and confronted with a rough reality principle; the lack of means leads to the use of influence and pressure, with the risk of emergence of conflicts and rivalry. The “networking” policy is then considerably threatened. This being underlined, Figure 1 proposes an algorithm of the different possible frameworks of support for child abuse cases by distinguishing three main levels. The first level is to reach an amicable settlement between the various people concerned and the professionals contacted. The other two levels of framework involve the social field mediated through an authority in a broader sense. This is usually the case when the first level is insufficient or powerless to establish the plan of care. A lack of real collaboration is the main argument for mobilising the second level of framework. The Youth Assistance Service (SAJ) is contacted for any situation involving a minor in difficulty or in danger.

Experience shows that the evolution of society, family patterns and the practices of professionals call for a continuous questioning of the treatment model of situations where children are failed by those around them. The place of the third party and the relationship of authority are at the heart of the issue. If the legislator wished to allow the possibility of the medico-psychological treatment of cases of abuse, it is clear that we would encounter positive results for not calling in the judicial authorities, as well as negative repercussions of this “non-judicialisation”. We have expanded on this discussion elsewhere [24].

The treatment phase

Therapeutic time follows the diagnostic assessment phase which is concluded with proposals for help and care. The treatment will depend not only on the actual abuse but on the traumatic impact on the child concerned and those around him. In this regard, we are confronted with a diversity of displays ranging from an absence of any symptomatology reflecting resilience, to the appearance of self-destructive behaviours that may lead to attempted suicide [1], with many other displays in between, such as somatisation or the appearance of severe psychiatric disorders. It is indeed important to remember that any abuse causes stress, the variations of which can translate into the broad spectrum of anxiety-depressive disorders [25], or even psychotic disorders. The onset and evolution of a disorder depends on one hand on biological, psychological, family, societal and cultural risk factors that interact with synergy and, on the other hand, the period of development during which these events take place and factors arise [26]. Thus, the same factors may have different effects depending on the timing and duration of their event. The therapeutic accompaniment of the abused child and those around him will be guided by the conclusions of the evaluative phase and will be more effective through the (partial) separation of the different axes of care and assistance. Networking, based on the concept of “shared professional secrecy”, makes it possible to take into account individuals, families and social axes, involving cognitive, affective and relational levels. The methodology we developed twenty years ago still works; we make progress, as mentioned in the case reports, by waves of successive meetings. Individual interviews precede group and family meetings. It is crucial to recognise that time must be given and that therapeutic management in situations of sexual polytrauma will require flexibility, adaptability, and creativity on the part of clinicians. The oscillation in the investment of the people concerned, the rising of anxieties, the stand-off periods, and the transferential movements, which are sometimes massive and aggressive, represents the stakes of a treatment, the temporality of which is established in months and, sometimes, in years. The question of stopping the therapeutic phase is also a source of anxiety as it recalls the problematic aspects of the link with those providing treatment. Let’s also be aware of the limits in mobilisation possibilities, especially where the family is experiencing chronic instability. Very often we will come up against dead ends, threats, and headlong rushes, leaving us unsatisfied. In addition, the case of the “depressive family” that we described twenty years ago, bringing together father, mother and child(ren), now represents very few of the situations amongst all families encountered [2]. Moreover, if interviews based on psychodynamic and systemic therapies remain the points of reference, we need to recognise the importance of specific approaches in the trauma clinic. EMDR and hypnosis incontestably constitute therapies appreciated by both children and adults, allowing the easing and amendment of debilitating symptoms, and emotional re-mobilisation at the level of cerebral functions seems to be a means of introducing analytical and/or systemic therapy when necessary. Depending on the situation, it is recommended to send a young patient, or a parent, “frozen” in their trauma, to a therapist practicing EMDR, always as part of a complex working group that also includes traditional contacts, couples, siblings or family. To remain coherent in managing this, it is necessary to know the recommendation and the limits of each approach, ensuring the principle of collegiate complementarity. It is certainly an evolutionary point, compared to our 1997 reflections, that shows the benefit of mobilising the different therapeutic approaches to be put in place around the child and his environment [27].

Figure 1: Intervention framework algorithm.

In order to avoid the fallout of social and economic exposure in the public domain and the phenomena of stigmatisation, Belgium opted for the possibility and not the obligation to call in the judiciary system, setting up multidisciplinary teams to assess and deal with situations of child abuse. Some would say that it is a “theory of least evil”. Admittedly, “non-judicialisation” involves pitfalls. As we have mentioned, the perversion of the social bond of our societies dominated by consumerism and individualism, and the maintenance of interventions in the medico-psycho-social field certainly increase the risk of some individuals exploiting the system, not hesitating to challenge its frames and limits [28].The absence of punishment can also reinforce a feeling of omnipotence likely to bring the aggressor to recidivism. And the clinician cannot guarantee non-recidivism [29]. As we have pointed out, our societies evolve and we are seeing a certain decay of authority in general. In comparison with the serious transgression of child abuse, it is not easy today to identify or create a symbolic figure of authority in the medico-psycho-social field. Thus, at a time when members of the judiciary have lost, for many individuals, their symbolic function of authority, can we conceive that the clinician occupies several roles to ensure a social control function? Ultimately, however, we advocate a case-by-case consideration based on multidisciplinary reflection and network practices.

- De Becker E, Marie AM. Le devenir de l’enfant victime de maltraitance sexuelle. Annales Médico-Psychologiques. 2015; 173: 805-814.

- Hayez JY, Emmanuel de B. L’enfant victime d’abus sexuel et sa famille. Evaluation et traitements. Paris: PUF. 1997.

- Haesevoets YH. Regard pluriel sur la maltraitance des enfants (Kluwer Ed.). Belgique. 2003.

- Haesevoets YH. L'enfant victime d'inceste. De la séduction traumatique à la violence sexuelle: De Boeck. 2015.

- Kempe RS, Henry et Ruth. L’enfance torturée. Bruxelles Mardaga. 1978.

- Strauss PMM, et al. L’enfant maltraité. Paris: Fleurus.1982.

- Furniss T, Bingley-Miller L, Bentovim A. Therapeutic approach to sexual abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984; 59: 865-870. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1628703/

- Sgroi SM. l’agression sexuelle et l’enfant. Trécarré Saint-Laurent Canada. 1986.

- Colette-Basecqz N. Le secret professionnel face a’ l’enfance maltraitée. Annales de Droit de Louvain. 2002; 62: 3-30.

- Robin P. L’évaluation de la maltraitance: comment prendre en compte la perspective de l’enfant? (PUR Ed.). Rennes. 2013.

- Ehrenberg A. La Société du malaise. Paris: Odile Jacob. 2012.

- Braconnier A. Optimiste (Odile Jacob ed.). Paris. 2015.

- Bonnet G. La perversion, se venger pour survivre. Paris. 2008.

- Barbier D. La fabrique de l’homme pervers. Paris: Odile Jacobs. 2013.

- Nazare-Aga I. 2004.

- Berger M. Voulons-nous des enfants barbares? Paris Dunod. 2008.

- Lebrun JP. Un monde sans limite. Paris: Eres. 2011.

- Odebrecht S, Maria Angelica EW, Watanable MAE, Morimoto HK, Moriya AR, et al. The impact of childhood sexual abuse on activation of immunological and neuroendocrine response. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010; 15: 440-445.

- Schraufnagel TJ, Kelly CD, George WH, Norris SJ. Childhood sexual abuse in males and subsequent risky sexual behaviour: A potential alcohol-use pathway. Child Abuse Negl. 2010; 34: 369-378.

- Trickett PK, Noll JG., Putnam FW. The impact of sexual abuse on female development: Lessons from a multigenerational, longitudinal research study. Dev Psychopathol. 2011; 23: 453-476. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23786689

- Barudy D. De la bientraitance infantile. France: Fabert. 2007.

- Hayez JY, Emmanuel de B. La parole de l’enfant en souffrance: accueillir, évaluer et accompagner. Paris: Dunod. 2010.

- Parret C. Accompagner l’enfant maltraité et sa famille. Paris: Dunod. 2006.

- Berger M, Emmanuel de B, Nathalie C. L’abus sexuel intrafamilial: discussion médico-psycho-juridique sur la pertinence du modèle de prise en charge. Acta Psychiatrica Belgica. 2015; 1 : 24-31.

- Monzee J. psychothérapie du développement affectif de l’enfant: Liber. 2014.

- Ogloff JRP, CM C, Mann E, Mullen P. Child sexual abuse and subsequent offending and victimisation: A 45 year follow-up study. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. 2012; 440.

- Berlin JL, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Dev. 2011; 82: 162-176. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21291435

- Godelier M. Métamorphoses de la parenté: Fayard. 2004.

- Cirillo S. Mauvais parents: comment leur venir en aide? France: Fabert. 2006.