More Information

Submitted: May 18, 2022 | Approved: May 30, 2022 | Published: May 31, 2022

How to cite this article: Azeez R, Veldmeijer C, Lomax P, O’Brien A. The surrey county lunatic asylum-an overview of some of the first admissions in 1863-1867. Arch Psychiatr Ment Health. 2022; 6: 023-028.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001039

Copyright License: © 2022 Azeez R, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The surrey county lunatic asylum-an overview of some of the first admissions in 1863-1867

Ruckshana Azeez* , Claire Veldmeijer, Paul Lomax and Aileen O’Brien

, Claire Veldmeijer, Paul Lomax and Aileen O’Brien

South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust, 61 Glenburnie Road, Tooting, SW17 7DJ, England

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Ruckshana Azeez, South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust, 61 Glenburnie Road, Tooting, SW17 7DJ, England, Email: [email protected]

In the 19th Century in much of Western Europe and North America the number and size of asylums increased hugely. In London, there was a wave of new asylums built in response to the 1808 County Asylums Act and the 1845 Lunacy Act, which required publicly funded care for those deemed mentally unwell. One such asylum was the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum which was built on the grounds which now house Springfield University Hospital in South West London.

This paper describes the admission records from Surrey County Lunatic Asylum, between 1863-1867, from information stored in the London Metropolitan Archives.

Although the terminology is different from that of today’s, the picture the records paint is of an institution aiming at recovery rather than long-term incarceration which can be how asylums are now remembered. This more nuanced view is starting to be discussed more in public conversations about the topic. The optimism this may imbue is tempered by the shocking number of patients who died within the institution.

Until the 19th century in England it has been suggested mental illness was hidden from society: they wandered the streets; were looked after by family or were placed in private “madhouses” and jails [1]. There were few options for public care. The 19th century was a turning point; asylums were built in response to new laws compelling authorities to provide a therapeutic environment for those who were mentally unwell [2].

The Surrey County Lunatic Asylum was one of these publicly funded asylums, built in response to The County Asylums Act 1808 which required each county to found and fund an asylum. It was established in 1838 on the site of Springfield Park in Wandsworth.

It was the fifteenth asylum to be built and initially had just 350 beds. It opened on 14th June 1841 with 299 patients being admitted on that day, many of whom were re-housed from other, frequently private, asylums. Over the next few years, with increasing demand, the hospital was extended and at maximum capacity, it could accommodate 2177 patients [3].

In 1999 the trust was renamed South West London and St Georges Mental Health NHS Trust, as it is known today. The current Trust is spread over 3 main inpatient sites; serving the boroughs of Richmond, Kingston, Merton, Sutton, and Wandsworth. The historical Asylum covered this area with the addition of rural Surrey.

The Lunacy Act of 1845 required all asylums to keep a record book, detailing each admission. These records provide an insight into the beginnings of the state’s provision of mental health care, by providing demographic data, illness details, and outcomes of those admitted. The records are currently stored in the London metropolitan archives.

Aims

By analyzing the records in the admission book from the Surrey Country Lunatic Asylum, we aimed to generate a picture of the type of people and illnesses that the institution cared for. This picture will allow us to discuss how mental illness presented and was managed in comparison to what we see today.

The Surrey County Lunatic Asylum admission records are kept in the London Metropolitan Archives, with separate admission books for males and females.

Male admission records were available and recorded between December 1858 and January 1872. Female admission records were available between June 1862 and Feb 1875. The period reviewed was the earliest records of both sexes were available.

Information in the records was:

- Dates of admission

- Basic demographic data – age and gender,

- Diagnosis

- Age at first diagnosis

- Duration of illness

- Cause of admission

- Date of discharge or date of death and outcome

‘Duration of Illness’ was the length of time since the start of the current episode. ‘Cause of admission’ appears to describe a precipitating event to the current illness rather than an underlying diagnosis. ‘Outcome’ of the admission was recorded as one of four alternatives; “Recovered”, “Relieved”, “Not improved”, or “Died”- where relieved appears to mean partial recovery.

Because of the separate recording of male and female data, these data were considered separately.

Anonymized records, which are freely available in the public domain, were used to gather information; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Information obtained included:

- Age

- Gender

- Length of admission

- Diagnosis

In addition, broad admission data was obtained for the local mental health trust that sits on the site of the old asylum.

710 patients were admitted to the asylum between 1863 and 1867.

Age and gender

There were:

- 290 female admissions

- 420 male admissions

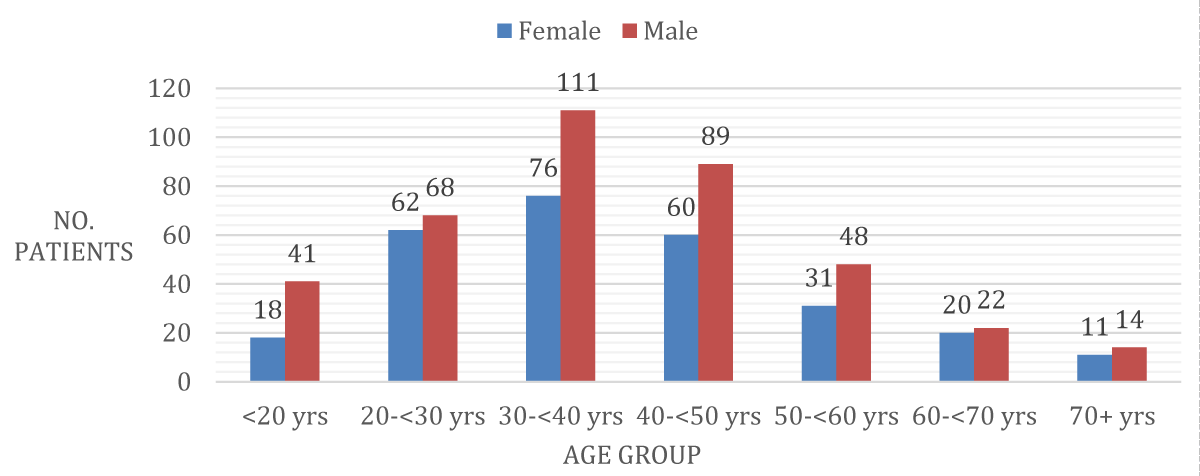

Most admissions were in the age bracket 30-40 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Sex and Age at Admission.

Diagnosis

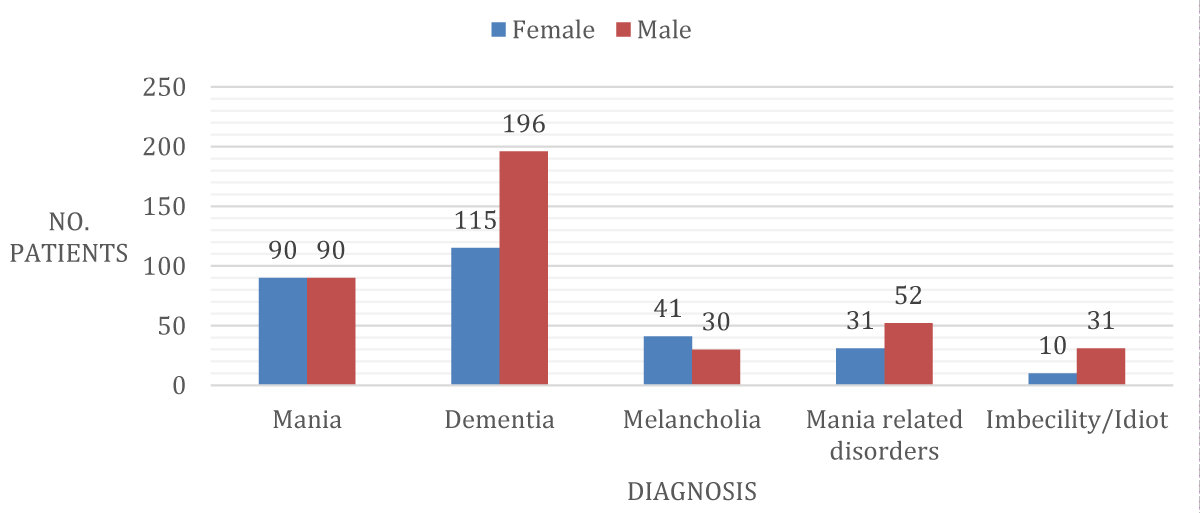

‘Mania’ and ‘Dementia’ were the most common recorded diagnoses. Dementia was recorded in 39% of females and 47% of males. 31% of females were given the diagnosis of mania, and 21% of males. There was also a category of mania-related diagnoses which included mania with delusions, recurrent mania, and hysterical mania.

There were also other diagnoses made but in comparatively few numbers. Notable other diagnoses were: “imbecility/idiot” (10 female patients and 31 male patients); “Dementia with General Paralysis” (1 female patient and 7 male patients); “Dementia with Epilepsy” (4 male patients); “Senile Dementia” (1 female patient and 3 male patients); “Delirium tremens” (1 male patient) and “No Indication of Insanity” (5 male patients) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Diagnosis recorded between 1863-1867.

Duration of illness

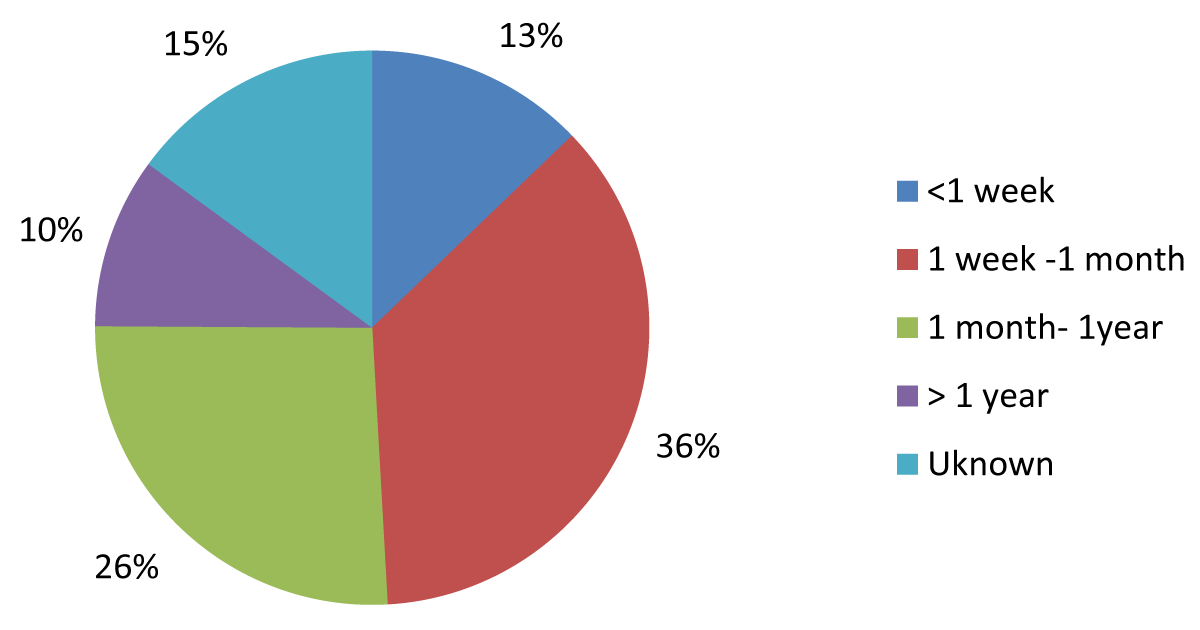

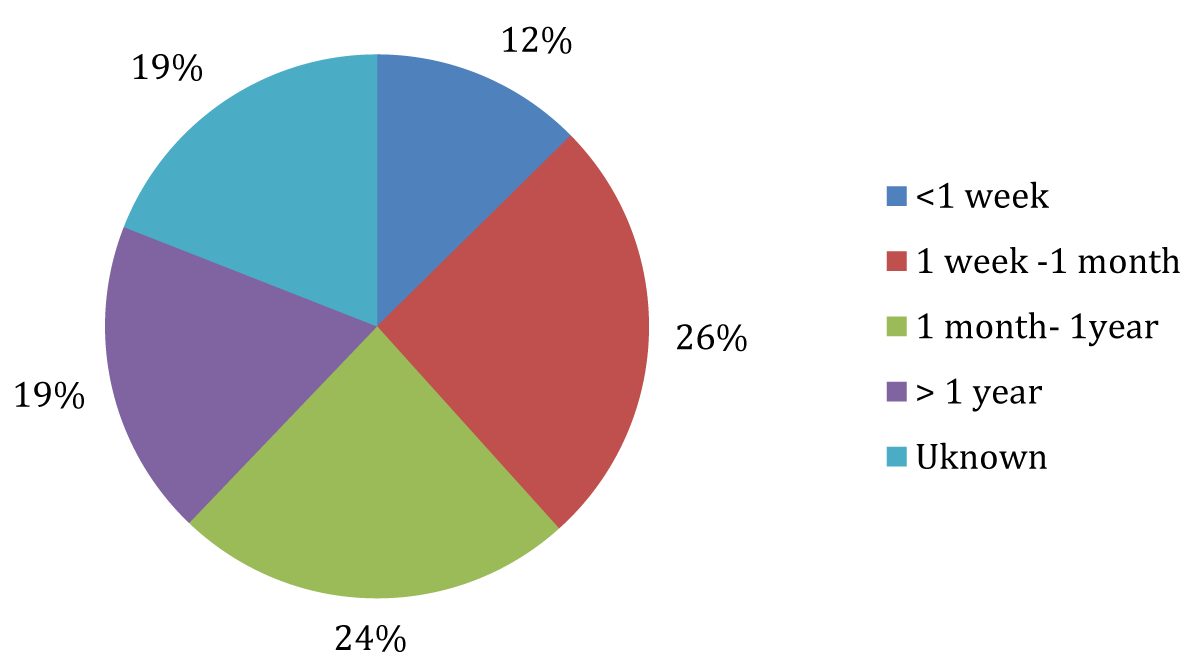

The most common period of illness before admission was between 1-week and 1-month (with 36% of females suffering for this period and 26 % of males). This was closely followed by the 1-month to 1-year category (26% of females and 24% of males). 75% of female patients and 62% of male patients in the 5-year period studied were ill for a period less than 6 months and 49% of female patients and 38% of male patients for a period less than 1 month (Figures 3,4).

Figure 3: Duration of illness in Females.

Figure 4: Duration of illness in Males.

Reason for admission

The admission records detailed the reason for admission, however, 71% of females and 68% of males were recorded as having an unknown reason for admission.

For those with a cause identified, the most common causes identified for men were “drink”, making up 6% of the total and physical accidents at 5%, whilst for women they were fits/epilepsy at 3% and “domestic troubles” 3%.

Other examples recorded include; “Loss of family member” 2% of females, “Fright” 1.4% of females, “Religion” 1.4% of females, “Hereditary” 1.7% of males and 1.4% of females, “Congenital” 2.9% of males and “syphilis” 1% of females.

There were some causes of admission for female patients that were not featured in the list for males and these included domestic troubles, illegitimate childbirth, disappointment in love, and hysteria. Male patients similarly have specific causes for admission that were not seen in the female population; including masturbation, sunstroke, heart attack, and bad eyes.

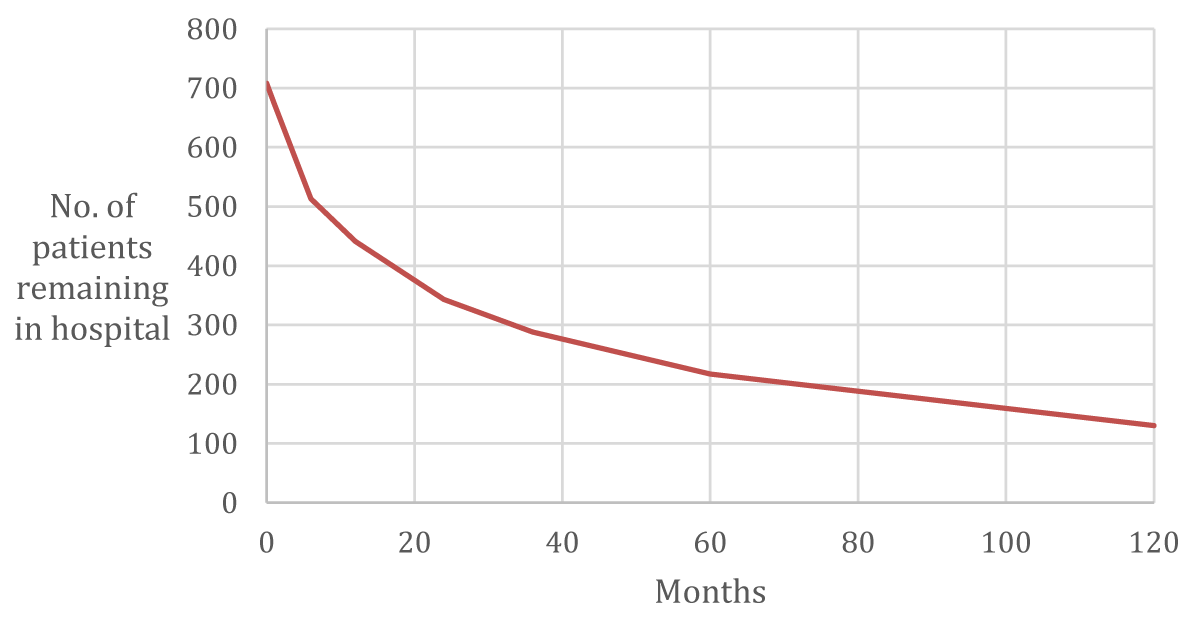

Duration of admission

Of those who survived to discharge, 23% were discharged prior to 6 months with 38% of all admissions being admitted for a total of less than a year and a half being discharged by 2 years.

There does appear to be a group of patients who were kept in the asylum for significantly longer periods with 18% of the admissions remaining in hospital for over 10 years and 11% for over 20 years. 10-30 year admissions were seen in 22% of the female patients and 14% of the male patients (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Length of Admission.

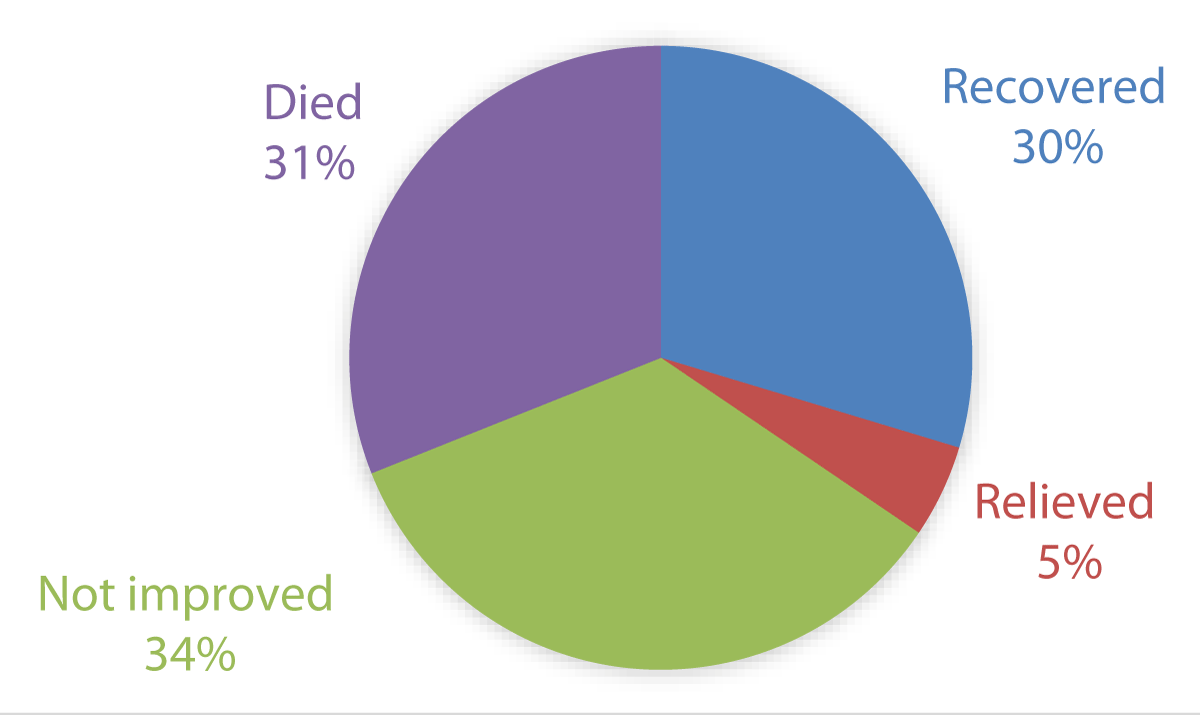

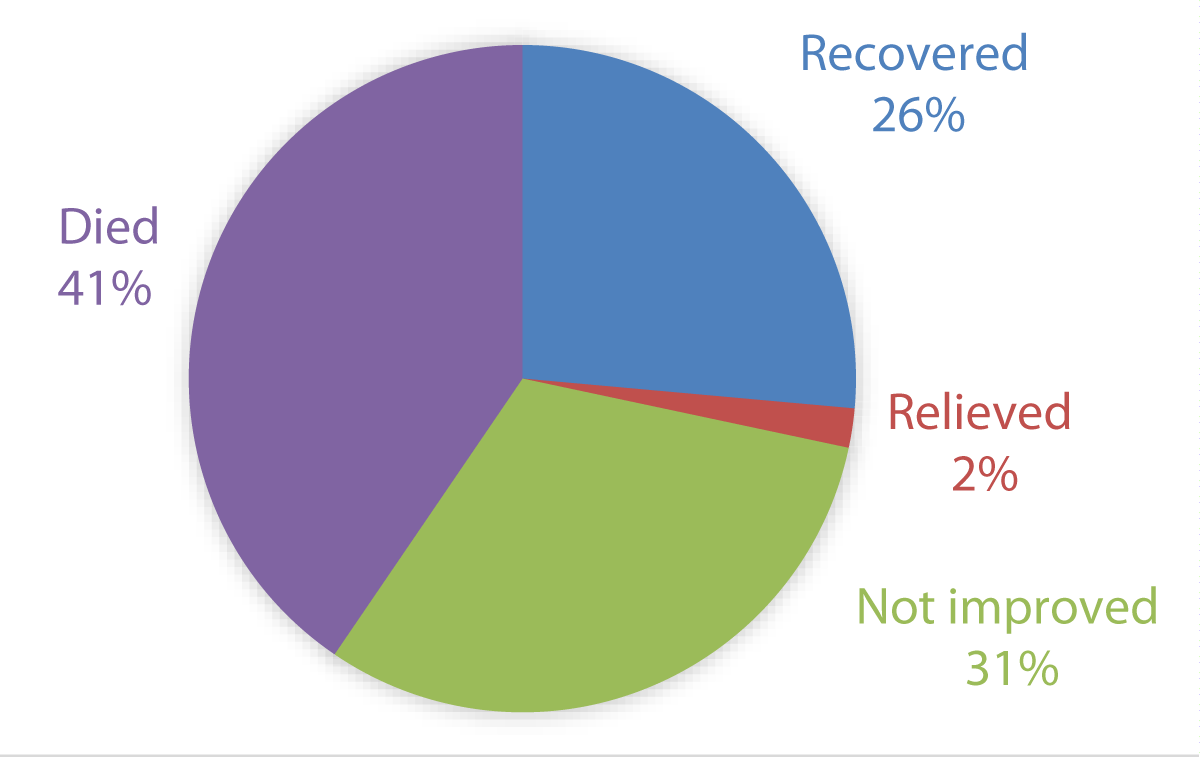

Outcome

There were 4 outcomes recorded for the patients; death in the asylum, recovery, relief, or no improvement. In the female group, the most common outcome was not improved on discharge making up 35%, 31% of the female group died during their time in the asylum and 30% were deemed to have recovered. In the male patient group, the most common outcome was death during the admission at 41% with 31% showing no improvement and 26% recovering (Figures 6,7).

Figure 6: Outcome of Female Admissions.

Figure 7: Outcome of Male Admissions.

Number of admissions

In the 5 years considered there were 710 admissions. Comparative data over a 5-year period in the contemporary mental health trust showed 8208 admissions. This is despite a similar number of people living in the catchment area of the respective organizations.

Sex

In the asylum era, there was a belief that women were more likely to be patients as ‘insanity’ was considered a predominately female problem [4]. However, the admission records from the asylum showed a higher rate of admission for males. We do not have details on the breakdown of the local population at the time so this may be representative of the population in the surrounding areas at the time with increasing areas of urbanization possibly attracting more males. In contemporary data of the area, the proportion of admissions was equally divided between the sexes, with 49.6% female admissions and 50.4% males.

Admission age

For most of the patients admitted during the asylum era, this was their first admission. This would suggest that the peak age of admission would be representative of the age of onset of a mental illness. The peak age of admission for both males and females occurred between 30-40 years of age, suggesting an onset in this period. Contemporary data shows that the peak age of detention under the MHA today is 18-34 [5], however, the late-life second peak seen in modern data for over 65s is not reflected in the historical data. This is not surprising given that life expectancy at that time was less than 50.

Diagnoses

The diagnoses recorded in the asylum admission book are difficult to interpret as they are not accompanied by symptoms and classification. The most common diagnoses are ‘Dementia’ and ‘Mania’. Similar diagnoses were found in similar records from an asylum in South West England, however, it was noted in that analysis that diagnostic terminology varied across the country [6].

A precise transfer of 19th-century diagnostic terminology to contemporary terminology is likely to be inaccurate. It has been held that the term “dementia” represents something similar to the contemporary diagnoses of Schizophrenia [7] whilst later in the century Kraepelin would differentiate Mania from such a dementia praecox along the current lines of a manic episode and a schizophrenic psychosis. If true, this dichotomy may have been established in practice 20 years before Kraepelin’s work [8]. It is also notable that there is no identifiable diagnosis that would correlate with a personality disorder.

Idiocy and imbecility were diagnoses documented, although clearly offensive terms, it is likely they represent people with intellectual disabilities [9]. These patients were often younger, but it was commonplace for these patients to be onwards with those suffering from dementia, mania, and melancholia [10]. It was not until over 30 years later that there was a separation of patients with intellectual disabilities from those suffering from a mental illness., when a separate ward was built on the same grounds [11]. Although not explicitly stated in the records it is very likely that the longer stay admissions included the those with intellectual disabilities who stayed as inpatients as there was no other acceptable place for them to reside in society during this time in history.

Cause of admission

In the asylum records, for the majority of patients, a cause was not recorded. It may be that it was only recorded where an obvious trigger was identified, however, the terminology used does not necessarily support this. The number of people where a specific cause was identified makes it hard to establish trends or patterns.

The most frequently recorded cause is alcohol consumption in men, followed by accidents. This fits with the pattern of substance misuse and risk-taking behavior that we see today, however, in what way alcohol consumption caused the admission is unclear. Shorter’s book gives an insight into a similar pattern of psychiatric conditions linked to alcohol consumption including alcohol withdrawal psychosis; Korsakoff syndrome and Wernicke’s encephalopathy [12].

Another cause noted is epilepsy, an illness today that would be treated by a neurologist. In the 1800s the pharmacological treatment of epilepsy was limited, and therefore, the sequela was that patients developed psychiatric complications such as mania and confusion [13].

A recorded but rare reason for admission was syphilis, with just 3 females and no males. There were also 8 diagnoses of Dementia with General Paralysis - likely another term for advanced syphilis which was often referred to as General Paralysis of the Insane [18,19]. It was seen increasingly during the Victorian era and associated with increasing asylum populations. After the turn of the century, syphilis was acknowledged to be responsible for 20% of admissions in some asylums [14], however, as with other data around asylum admissions [15], the identification of it as a cause was infrequent during this period.

Admission and treatment

Contrary to the view that asylums were a place where people spent many years [16], the data shows that most patients were discharged within 2 years. That being said, such a timeframe was still much longer than in the recent data where a long stay in hospital is defined as greater than 21 days [17] .

The admission and treatment profile appears unusual to a contemporary practitioner. Admissions appear to have been relatively quick with over 40% being admitted within 1 month of the onset of their symptoms and there appear to be very low readmission rates at 7%.

This low re-admission picture in the asylum may be explained in a number of ways. The starkest is that around a third of people admitted to the asylum died whilst in the institution. Another third were discharged “not improved” which suggests that asylums were not seen as long-term accommodation options for people with chronic mental illness but as a place for a potential cure. The group of patients that were “not improved” by their stay would be unlikely to be funded for re-admission. Modern pharmaceutical treatments for psychosis may be seen to enable a rapid reduction in symptoms followed by potential relapse at a later date. The lack of this option in the 19th century may be the reason for the longer stays in the hospital, the high proportion discharged as not improved, and the low re-admission rates.

Duration of illness

This was the duration that a patient was unwell before being admitted. The admission process involved two doctors separately determining whether the individual was deemed “a lunatic” [18]. The 1-week to 1-month timeframe was the most frequent. This suggests that individuals were admitted quite soon after the onset of illness. One reason for these prompt admissions could be low tolerance from family members to care for the mentally unwell may be due to reduced family networks in the rapidly urbanizing society [19]. Another theory for this could be that the presence of the asylum meant that people readily turned to the asylum in the hope of a cure, suggesting that such institutions were looked upon favorably by society.

Inpatient deaths

A high inpatient death rate was readily apparent in the records. 31% of females and 41% of males died as an inpatient. The proportion of men dying is higher, possibly reflecting the greater proportion of physical accidents or alcohol precipitating their admission.

The proportion of people who died in hospital appears the most alien aspect of the data to modern eyes. Unfortunately for most of these no cause of death was recorded. Of those that were recorded very few were attributed to suicide and most appeared linked to common diseases of the time such as “dropsy” and “pleurisy”. There were frequent references to “maniacal exhaustion” as a cause of death.

Examples are found elsewhere to raise the possibility of treatments playing a role in this high mortality. In 1857 Daniel Dolley, a 65-year-old mole catcher, was admitted. He was described as being “excited and overactive”. On one occasion when Daniel kicked another patient and hit the attending doctor, a shower bath lasting at least half an hour was administered followed by 2 grains of antimony tartrate. Dolley suffered a seizure and subsequently died [20]. Whether this was an isolated case or a regular occurrence is not clear, however, the contemporary controversy suggests it may be unusual.

It must be remembered that the life expectancy during this time was shorter around 50 years old. There was also a significant minority of patients in who remained in the hospital for a large length of time (130 of the 710 admissions remained for greater than 10 years) raising the possibility of ‘natural’ deaths whilst in hospital.

As we were using historical data, we were restricted to looking into categories of information that were recorded at the time.

There was a limited timeframe of data we could look into that overlapped between the two genders. It is not clear why this difference in data recording exists but it limited the time frame of data available to review.

Unfortunately, due to the Anonymised nature of the records, we were unable to cross-check deaths with publicly available death certificates which would have provided us with more specific data for comparison.

To some degree, language has changed over the past 170-180 years and the vocabulary used in the record books does not always comparable to that used today. What was recorded then were historical concepts as opposed to formal diagnosis as per diagnostic criteria? Although a dictionary of psychological medicine was used to determine some of the language used, it is open to interpretation.

This piece of work has provided information about the early years in the history of inpatient mental health care specifically at the establishment. The aim of this research was primarily exploratory.

The most common recorded diagnosis was “dementia” and “mania” and it is clear that these diagnoses do not translate to the modern-day use of those diagnostic terms but may represent the dichotomy of psychoses that Kraepelin would famously describe 30 years later.

What we find is an institution designed to cure people, which may counter our prejudices that such places were merely to separate people with mental illness from society. This nuanced view of the Victorian asylum is more widely appreciated in recent years in public debate [21]. People did remain in the hospital for longer but the re-admission rate was much reduced raising the possibility that such illnesses may have a similar course to those we see today but that the reaction of services today is more of a ‘revolving door’ to inpatient admissions which are shorter but more frequent.

Any suggestion that such an institution may have lessons for us must be tempered by the astonishing death rates seen where 1 in 3 admissions would die in the hospital.

- Shorter E., A History of Psychiatry: from the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1997

- Rogers A., Pilgrim D., Mental Health Policy in Britain. Second Edition. Hampshire: Palgrave; 2001

- Patch LI, The Surrey County Lunatic Asylum (Springfield): Early Years in the Development of an Institution. Bri J Psychiatry [Online]. 1991:159;69-77. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/159/1/69

- Busfield J., The Female Malady? Men, Women and Madness in Nineteenth Century Britain. Sociology [Online] 1994:28;259-277. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42855327

- https://files.digital.nhs.uk/00/66FBD2/ment-heal-act-stat-eng-2018-19-summ-rep.pdf

- Hill SA, Laugharne R., Mania, dementia and melancholia in the 1870s: admissions to a Cornwall asylum. J Royal Society Med.[Online] 2003:96;361- 363. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC539549/

- horter history of psychiatry page 62

- Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie in 1893.

- Shorter E., A History of Psychiatry: from the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1997

- Wright D, Digby A, (ed), From Idiocy to Mental Deficiency: Historical perspectives on people with learning disabilities [Online] New York: Routledge; 1996. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UcBr3g6yniIC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&dq=from+idiocy+to+mental+deficiency&source=bl&ots=ihN6ByU_PR&sig=fUtEdGcJa1bR5LpiFC0EIvVWX0I&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ZwTvVPvUJdDraMHYgZgL&ved=0CFAQ6AEwBw-v=onepage&q#v=onepage&q=fromidiocytomentaldeficiency&f=false

- Patch LI, The Surrey County Lunatic Asylum (Springfield): Early Years in the Development of an Institution. Bri J Psychiatry [Online] 1991;159;69-77. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/159/1/69

- Shorter E. A History of Psychiatry: from the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1997

- Gross RA, A brief history of epilepsy and its therapy in the western hemisphere. Epilepsy research [Online] 1992;12:65-74. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/092012119290028R

- Syphilis in the causation of insanity. British Medical Journal. [Online] 1914; 1(2773):434. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2300771/

- Hill S. A., Laugharne R., Mania, dementia and melancholia in the 1870s: admissions to a Cornwall asylum. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2003:96;361- 363.

- Wright D., Getting out of the Asylum: Understanding the Confinement of the Insane in the Nineteenth Century. The Society for the Social History of Medicine [Online] 1997; 10 (1): 137-155. http://shm.oxfordjournals.org/content/10/1/137.short?rss=1&ssource=mfc

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/urgent-emergency-care/reducing-length-of-stay/

- Wise S., Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad-Doctors in Victorian England. London: The Bodley Head; 2012

- Wright D., Getting out of the Asylum: Understanding the Confinement of the Insane in the Nineteenth Century. The Society for the Social History of Medicine [Online] 1997; 10 (1): 137-155. http://shm.oxfordjournals.org/content/10/1/137.short?rss=1&ssource=mfc

- Springfield a short history. Patch, Ian Lodge; Springfield hospital. 1985. Available at heritage service and Putney library store.

- https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/victorian-mental-asylum